History of u.s. marine corps forces, pacific

Established in 1944, U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Pacific, has a storied history dating back more than 75 years. General Holland M. Smith established the Headquarters, than Fleet Marine Forces-Pacific, directly under the U.S. Navy subordinate command, U.S. Pacific Fleet, in order to command and resource nearly 500,000 Pacific Marine Forces. At that time, FMF-PAC included six Marine divisions and five Aircraft Wings.

Administrative buildings located on Camp

Catlin, Hawaii, Dec. 29, 1945 |

FMF-PAC operated on Camp Catlin, Hawaii, until 1950 when the staff began looking for a more permanent location. In 1955, the command moved into the former Aiea Heights Naval Hospital that had completed constructed in 1942, with the first Marine residents taking post in October of 1955. The headquarters staff placed the camp in full operation just two weeks before its dedication on January 31, 1956.

In 1992, U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Pacific, was designated a service component headquarters, and the commander still maintains the role of FMF-PAC.

|

|

Since 1955, the commander, U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Pacific, leads, operates, and commands from the headquarters base, Camp H.M. Smith, Hawaii. The camp was named after Gen. Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith on June 8, 1955, in honor of his leadership during World War II, including leading Marines to victory in the island-hopping campaign across the Pacific, and for his successes in modernizing amphibious warfare.

Left: The Aiea Naval Hospital conducts an all-hands formation in front of the Aiea Heights Naval Hospital during World War II. On Jan. 1, 1944, Adm. Chester W. Nimitz ordered all able patients to assemble in front of the hospital in order to personally present the combat-wounded patients their awards. The building that currently headquarters U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Pacific was once the primary rear-area hospital for the Navy and Marine Corps during World War II.

|

The Aiea Naval Hospital |

U.S. Marines with 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, take cover after receiving contact in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, May 28, 2012. |

Following the September 11, 2001 attacks and the initiation of Operation Enduring Freedom, Lieutenant General Earl B. Hailston, Jr., commander, U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Pacific, was designated as commander, U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Central Command. Although tailored for operations in littoral environments, Lt. Gen. Hailston was tasked with establishing a Combined Joint Task Force-Consequence Management headquarters in Kuwait. Later, Lt. Gen. Hailston and his staff would oversee the deployment of more than 70,000 U.S. Marines and sailors to the CENTCOM AOR in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

|

|

In August of 2005, as the number of operations in the CENTCOM AOR increased, MARCENT was removed from the responsibilities of MARFORPAC and its commander, and a free standing headquarters was established as U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Central Command.

U.S. Marines in the Pacific are assigned to the commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, and operate across the INDOPACOM area of responsibility that contains two-thirds of the world's population, 43 countries, the world's six largest armed forces and crosses 16 time zones – more than half the Earth's surface.

|

U.S. Marines with Marine Rotational Force Darwin set up a defensive position during Exercise Koolendong, at the Royal Australian Air Force Base Curtin, WA, Australia, July 18, 2022. |

![U.S. Marines with A Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines [A/1/1] return fire from a house window during a search and clear mission in the battle of Hue, Feb. 1968. (Official USMC photo by Sergeant Bruce A. Atwell, Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections). U.S. Marines with A Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines [A/1/1] return fire from a house window during a search and clear mission in the battle of Hue, Feb. 1968. (Official USMC photo by Sergeant Bruce A. Atwell, Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections).](/portals/21/680201-M-HA123-800.jpg)

U.S. Marines with A Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines [A/1/1] return fire from a house window during a search and clear mission in the battle of Hue, Feb. 1968. |

Throughout its storied history, MARFORPAC has directly served in or supported various campaigns to include: the Pacific Island Campaigns, World War II, June 1944 to August 1945; the war in Korea, June 1950 to July 1953; the war in Vietnam, March 1965 to April 1975; Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm, Southwest Asia, August 1990 to April 1991; Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2003 to 2010, and Operation Enduring Freedom, Afghanistan, 2001 to 2021.

|

|

In addition to combat operations, MARFORPAC has responded in support of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations throughout the Indo-Pacific, to include: Operation Unified Assistance, Indonesia; Operation Sea Angel, Bangladesh; Operation Caring Response, Myanmar; Operation Tomodachi, Japan; Operation Sea Angel II, Bangladesh; Operation Damayan, Philippines; and Operation Sahayogi Haat, Nepal.

|

U.S. Marine Corps Col. John E. Merna, commanding officer, 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit, speaks with a Philippine Department of Social Welfare and Development worker during Operation Damayan, Leyte, Philippines, November 18, 2013. |

Today, the Marines and Sailors work diligently, supporting exercises, operations, and events alongside our allies and partners, ensuring we are committed, ready, and capable of carrying out any and every mission essential task called on to us throughout the free and open Indo-Pacific.

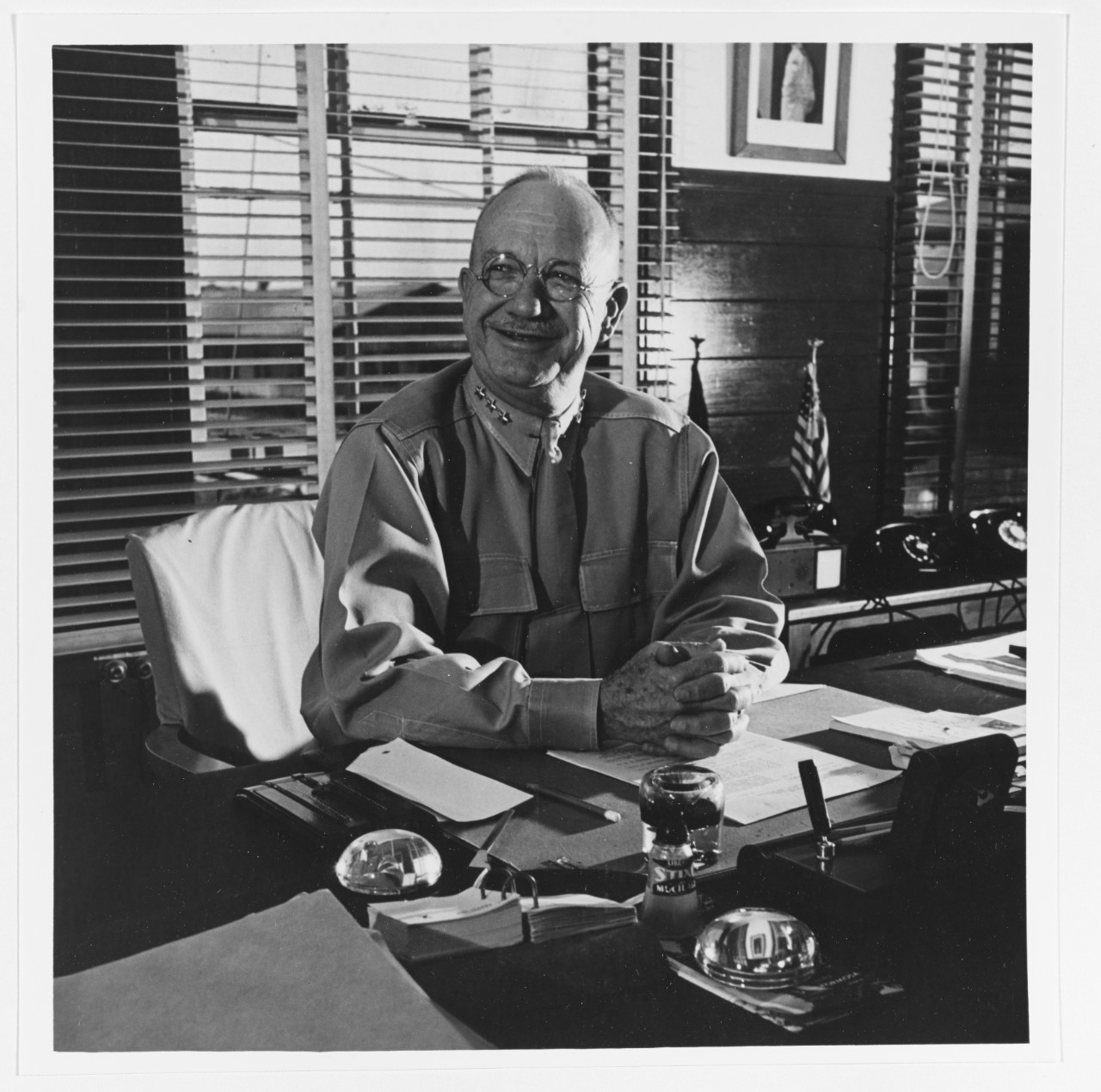

General holland m. smith

Born Holland McTyeire Smith in Seale, Alabama, April 20, 1882. Smith was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in April of 1906. Following his commission, he received his first orders to the First Marine Brigade, serving in the Philippines. In 1908, he was promoted to First Lieutenant and served at various Marine Barracks until September 1912 when he returned to the Philippines with the First Marine Brigade.

Born Holland McTyeire Smith in Seale, Alabama, April 20, 1882. Smith was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in April of 1906. Following his commission, he received his first orders to the First Marine Brigade, serving in the Philippines. In 1908, he was promoted to First Lieutenant and served at various Marine Barracks until September 1912 when he returned to the Philippines with the First Marine Brigade.

In June 1916, he was promoted to Captain and departed for temporary duty in the Dominican Republic Campaign with the Fourth Marine Regiment. During World War I, he served as Adjutant of the Fifth Marine Brigade in France and with the First Army during the occupation of Germany. In June 1920, he was promoted to Major and graduated from the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island. He then served at various east-coast duty stations before reporting to Washington, D.C. to serve in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations in the War and Plans Section, making him the first Marine to serve on a Joint Army-Navy Planning Committee.

Major Smith then reported as the Fleet Marine Officer onboard the USS Wyoming before transferring USS Arkansas. In the winter months of 1924, he served as the Chief of Staff and Officer in Charge of Operations and Training with the Marine Brigade in Haiti. In summer of 1925, he became the Chief of Staff of the First Marine Brigade in Quantico, Virginia.

Following this assignment, Major Smith was assigned as the Post Quartermaster for Marine Barracks, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In July of 1930, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and appointed as the Aide to the Commander and Force Marine Office of the Battle Force, U.S. Fleet on board USS California one year later, in 1931, before commanding Marine Barracks Washington, D.C.

In the spring of 1934, he was promoted to the rank of Colonel. At this rank, he held various positions to include: Chief of Staff to the Department of the Pacific, Director of the Division of Operations and Training, HQMC, and Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps.

In August of 1939, he was promoted to Brigadier General and appointed commander, First Marine Brigade. In June of 1941, he assisted in the creation of Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet, which provided initial training for the First Marines and the Ninth Army Division in amphibious warfare. In October of 1941, he was promoted to the rank of Major General.

In August of 1942, commanded the Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet, preparing the troops for amphibious operations in the Aleutian Islands. In November of 1943, he assisted in the planning for the invasions of Tarawa and the Gilbert Islands.

He was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General and following the invasion of Kwajalein and preparation for the invasions of Saipan, Guam, and Tinian, was designated commanding general, Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific. During this assignment he commanded Task Force 56, assisting in the planning for the Battle of Iwo Jima. His final assignment in the Marine Corps was leading the Marine Training and Replacement Command, Camp Pendleton, California.

On May 15, 1946, Lieutenant General Smith retired from the U.S. Marine Corps after 40 years of faithful service. He was subsequently promoted to the rank of General on the retired list three months later.

General Smith passed away on January 12, 1967, and was laid to rest in Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego, California.

In honor of his legacy and contributions to the development of amphibious warfare, Camp H.M. Smith, the headquarters of former Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific, now U.S. Marine Corps, Forces, Pacific, was named after him.

PACIFIC campaign | wwii

PRELUDE TO WAR

|

Japanese soldiers of 29th Regiment taking an offensive posture

on the Mukden Little West Gate, 19 Sep. 1931, Shenyang, China

|

After massive campaigns of expansion into mainland China, the Empire of Japan faced widespread international condemnation. As a result, the United States placed an oil embargo on Japan, and began reinforcing its pacific territories. Knowing that a war between countries would quickly turn to the U.S.’s favor, the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy decided to launch surprise attacks across the pacific, in order to gain the advantage and keep fighting away for the Japanese core territories.

|

december 7, 1941

|

On December 7, 1941, aircraft from the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked U.S. military installations on the Island of Oahu. Successive waves of aircraft were almost entirely unopposed, and only faced light resistance from the unsuspecting defending forces. The Japanese pilots scored heavily: four battleships, one mine layer, and a target ship sunk; four battleships, three cruisers, three destroyers, and three auxiliaries damaged. Most of the damaged ships required extensive repairs. American plane losses were equally high: 188 aircraft totally destroyed and 31 more damaged. The Navy and Marine Corps had 2,086 officers and men killed, the Army 194, as a result of the attack: 1,109 men of all the services survived their wounds. Balanced against the staggering American totals was a fantastically light tally sheet of Japanese losses. The enemy carriers recovered all but 29 of the planes they had sent out; ship losses amounted to five midget submarines; and less than a hundred men were killed. This attack, along with simultaneous attacks on U.S. forces across the pacific launched the United States and the U.S. Marine Corps in to World War II.

|

Photograph taken from a Japanese plane during the torpedo attack

on ships moored on both sides of Ford Island shortly after the

beginning of the Pearl Harbor attack. A torpedo has just hit USS

West Virginia on the far side of Ford Island (center).

|

The battle of wake island

december 8, 1941

|

A destroyed Japanese patrol boat (#33) on Wake Island.

|

At the same time that Marines and Sailors were defending Pearl Harbor, Marines with the 1st Defense Battalion and Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 211 were defending against another Imperial Japanese assault. Multiple Japanese fighter and bomber aircraft flying from the Marshall Islands attacked Wake Island, and shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched two separate amphibious landings. Despite being outnumbered and out of supplies, the Marines on the island managed to shoot down multiple attacking aircraft, and sink two Japanese destroyers. Eventually, the Imperial Japanese forces over ran the Marines’ defenses, and the Naval Officer in charge of the American forces on the island made the decision to surrender. Of the Marines who manned Wake's defenses, 49 were killed, 32 were wounded, and the remainder became prisoners of war. Of the 68 Navy officers and men, three were killed, five wounded, and the rest taken prisoner. Wake was not recaptured by American forces during the war.

|

guadalcanal

august 7, 1942 - february 9, 1942

|

After the stunning surprise attacks that had caught the United States off guard and resulted in the loss of thousands of American lives, the American public was desperate for good news concerning the war. The first American offense of the pacific war came on August 7, 1942, when Marines with the 1st Marine Division landed on Guadalcanal, and began a deadly, months long struggle for control of the island.

|

Guadalcanal, December 10, 1942. Marine SBD Squadron warms

up before strike at Henderson Field during December 1942.

|

Gilbert islands

November 20-23, 1943

|

Marines seek cover among the dead and wounded behind the

sea wall on Red Beach 3, Tarawa.

|

The Japanese loss of Apamama, Makin, Abaiang, Marakei, and Maiana Atolls did not cripple the Japanese’s ability to conduct operations in the pacific. Although the Imperial Japanese Navy had been badly beaten at the battle of Midway, their ability to supply island garrisons and maintain air parity was still a thorn in the side of American military planners. Admiral Nimitz and Admiral King knew that capturing the Marshall Islands was critical to placing the Japanese fully on the defensive. The capture of airfield sites in the Gilberts brought the Marshalls within more effective range of land-based aircraft. As a result of the Gilberts Islands campaign, the Army Air Forces gained four new airfields from which to launch strikes at targets in the Marshalls.

|

marshall islands

january 31 - february 23 1944

|

The conquest of the Marshalls was a far more significant victory than the previous success in the Gilberts. As far as the Japanese were concerned, the Marshalls themselves were not indispensable, but the speed with which the American forces moved robbed the enemy of the time he needed to prepare for the defense of the more vital islands that lay nearer to Japan. This dealt a major blow to the Imperial Japanese ability to conduct operations, and along with the decision to raid and then bypass Truk Atoll, set the stage for the final year of the Pacific Campaign, and the bloodiest battles of the pacific war.

|

Back to a Coast Guard assault transport comes this Marine after

two days and nights of Hell on the beach of Eniwetok in the

Marshall Islands. His face is grimey with coral dust but the

light of battle stays in his eyes.

|

guam

july 21 - august 10, 1944

|

First flag on Guam on boat hook mast. Two U.S. officers plant the

American flag on Guam eight minutes after U.S. Marines and Army

assault troops landed on the Central Pacific island on July 20, 1944.

|

The naval invasion of Guam was remarkable for the intense and calculated degree of naval and air bombardment preceding the landings. In the Palaus and the Philippines, at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, gunfire support ships never again had the opportunity for prolonged, systematic fire that was exploited so successfully at Guam. The destruction of Japanese positions led the naval gunfire officer to observe: “The extended period for bombardment plus a system for keeping target damage reports accounted for practically every known Japanese gun that could seriously endanger our landings.” While the landings were not without casualties, the naval gunfire was able to make a substantial difference in the success of the Marines’ attack.

|

iwo jima

february 16 - march 26, 1945

|

Even before ground operations to secure the Mariana Islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian ended, U.S. Naval construction battalions were already clearing land for air bases suitable for the new B-29 “Superfortresses.” These huge bombers had a range capable of reaching the Japanese Home Islands. The first B-29 bombing runs began in October 1944. But there was a problem— Japanese fighters taking off from tiny Iwo Jima were intercepting B29s, as well as attacking the Mariana airfields. The U.S. determined that Iwo Jima must be captured. U.S. Marines invaded Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, after months of naval and air bombardment. The Japanese defenders of the island were dug into bunkers deep within the volcanic rocks. Approximately 70,000 U.S. Marines and 18,000 Japanese soldiers took part in the battle. In thirty-six days of fighting on the island, nearly 7,000 U.S. Marines were killed. Another 20,000 were wounded. Marines captured 216 Japanese soldiers; the rest were killed in action. The island was finally declared secured on March 26, 1945. It had been one of the bloodiest battles in Marine Corps history. After the battle, Iwo Jima served as an emergency landing site for more than 2,200 B-29 bombers, saving the lives of 24,000 U.S. airmen. Securing Iwo Jima prepared the way for the last and largest battle in the Pacific: the invasion of Okinawa.

|

Six U.S. Marines raise the American flag on top of Mt. Suribachi,

Iwo Jima, 23 February, 1945.

|

okinawa

april 1 - june 22, 1945

|

Two Marines from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment during

fighting at Wana Ridge during the Battle of Okinawa, May 1945.

|

The island of Okinawa is the largest in the chain of islands known as the Ryukyus, which lie to the southwest of Japan. Taking Okinawa would provide Allied forces an airbase from which bombers could strike Japan and an advanced anchorage for Allied fleets. From Okinawa, US forces could increase air strikes against Japan and blockade important logistical routes, denying the home islands of vital commodities. Code named Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa and other islands in the Ryukyus began on April 1, 1945. Although the joint Army-Marine Corps landings on Okinawa were initially unopposed, the well dug-in Japanese defenders soon put-up fierce resistance. The battle for Okinawa drug out over nearly three months and included some of the worst kamikaze attacks of the war. By the time Okinawa was secured by American forces on June 22, 1945, the United States had sustained over 49,000 casualties including more than 12,500 men killed or missing. Okinawans caught in the fighting suffered greatly, with an estimate as high as 150,000 civilians killed. Of the Japanese defending the island, an estimated 110,000 died. Twenty-four American military personnel were awarded the Medal of Honor for going above and beyond the call of duty. In American hands, the island provided a vital airfield in the final drive on Japan, as the Allies finally brought about Japanese surrender less than three months later.

|

japanese Surrender

september 2, 1945

|

As the final culmination of the allied bombing campaign in Japan, the United States dropped nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th respectively. Six days later, on 15 August 1945, the Emperor of Japan made the final decision to surrender to the allies and bring an end to the pacific war. This monumental decision put an end to the United States’ Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands. Estimated casualties for the invasion had been almost a million battle field deaths for the allied forces, and many times that number for Japanese civilians. On 2 September 1945, the Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu and Admiral Chester Nimitz signed the official Japanese Instrument of Surrender, along with more than a dozen other representatives from the Japanese and allied delegations. With the signing of the surrender, World War II was finally brought to an end, and the most deadly conflict in world history was concluded.

|

Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the

Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Japanese Government,

on board USS Missouri (BB-63), 2 September 1945.

|

Guadalcanal campaign | wwii

The Guadalcanal Campaign: 7 Aug 1942—8 Feb 1943

Approximately 44,000 members of the U.S. armed forces fought in the Guadalcanal Campaign, of which nearly 11,000 were Marines. These forces fought alongside Solomon Islanders, Allies, and partners against approximately 31,000 soldiers and sailors of the Empire of Japan. Over the course of the campaign, there were approximately 1,600 U.S. KIA, and several thousand other WIA and approximately 24,000 Japanese KIA. The Allies that fought alongside U.S. forces included the Solomon Islands, Australia, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Tonga, and Fiji. The Allied success in Guadalcanal ended Japanese expansion efforts in the Pacific and placed the Allies in a position of supremacy. The victory at Guadalcanal could be seen as the first in a string of successes that eventually led to the surrender of Imperial Japan.

amphibious landing on guadalcanal

August 7, 1942

|

The battle began with a 1st Marine Division amphibious landing on August 7, 1942 – exactly eight months after the attack on Pearl Harbor – and lasted until the Japanese withdrew from the island in early February of 1943. The amphibious landing marked the first amphibious assault made against enemy forces by the 1st Marine Division.

Commanded by then-Major General Alexander Vandegrift, the 1st Marine Division was chosen to make the amphibious landing on Guadalcanal and seize a strategic airfield, with the intent of halting the advance of Imperial Japanese forces. After bypassing enemy patrol aircraft due to obscuring weather conditions, the 5th Marine Regiment of 1st MARDIV landed on Red Beach with little enemy resistance and took a defensive position.

|

U.S. First Division Marines storm ashore across Guadalcanal's beaches on D-Day, August 7, 1942

|

Guadalcanal, December 10, 1942. Marine SBD Squadron warms up before strike at Henderson Field during December 1942.

|

Under the support of 5th Marines and U.S. Naval gunfire, the 1st Marine Regiment landed ashore, advancing past the beachhead. Shortly after, battalions of both the 1st and 5th Marine Regiments maneuvered to the Lunga Point airfield – later named Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson, an aviator killed at the Battle of Midway – securing that critical objective on August 8, 1942.

Shortly after the U.S. Marines seized Henderson Field, Imperial Japanese forces responded with an intense campaign in the air, land, and sea, attempting to regain control of that key element to continued Allied strength in the region. In the face of unforgiving weather, logistical challenges, disease, and treacherous terrain, U.S. forces maintained control of the airfield in the face of sophisticated attacks intended to drive Marine forces from the island altogether.

|

During the night of February 7, 1943, the last Imperial Japanese forces were evacuated from Guadalcanal by a destroyer task force as part of Operation Ke. This marked the end of the fight for Guadalcanal, a battle that claimed the lives of more than 38,000 combined troops, marking one of the first Allied victories in the Pacific.

The battle of savo island

August 9, 1942

|

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Imperial Japanese Navy undertook a night surface attack on the ships screening the Allied landing force. The battle has come to be identified as the worst defeat in a single fleet action suffered by the United States Navy.

After the 1st Marine Division landed on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Navy launched a night assault against the Allied Naval Task Force supporting the invasion. The Japanese task force, consisting of seven cruisers and one destroyer sailed from Rabaul, New Britain, and Kavieng, New Ireland, down New Georgia Sound.

|

|

|

Catching the allied task force off guard, the Japanese were able to cause major damage to the allied force, sinking one Australian and three American cruisers. During the engagement, 1,023 allied personnel were killed, and another 709 were wounded. Despite the terrible casualties on the allied side, the Japanese force received only light damage during the battle. The Japanese did not realize the full superiority of their position, and did not press on to destroy the allied transport ships.

Had they done so, the Marines on Guadalcanal would have been entirely unsupported, and possibly might not have won the land battle. Immediately following their victory over the allied task force, the Japanese began bombing the Marines on the island of Guadalcanal. The Battle of Savo Island is widely considered to be one of the worst naval defeats in American history, and placed the entire allied Guadalcanal Campaign in jeopardy.

|

The USS Quincy (CA-39), burning and illuminated by Japanese searchlights, during the Battle of Savo Island off the coast of Guadalcanal, August 9, 1942. The USS Quincy (CA-39), burning and illuminated by Japanese searchlights, during the Battle of Savo Island off the coast of Guadalcanal, August 9, 1942. |

battle of tenaru

August 23-25, 1942

The Battle of Tenaru, also known as the Battle of Ilu River or the Battle of Alligator Creek, was the first of three major Japanese ground offensive operations during the Guadalcanal Campaign. The 2nd Battalion, 28th Infantry Regiment (Rein.), also known as the Ichiki Detachment, led the assault against the fox-holed Marine forces defending the Lunga perimeter, which guarded Henderson Field.

Tenaru River, Guadalcanal, circa 1942 From the collection of Clifton B. Cates (COLL/3157) United States Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections

|

The Ichiki Detachment attempted a night-time frontal assault against the Marine forces on the east side of the Lunga perimeter, but were spotted by Jacob Vouza, a Solomon Island police officer and Coastwatcher scout, who informed the Marines moments before the attack took place. This battle also represents the first attempted Banzai charge by Japanese forces against an American unit during the Pacific War.

|

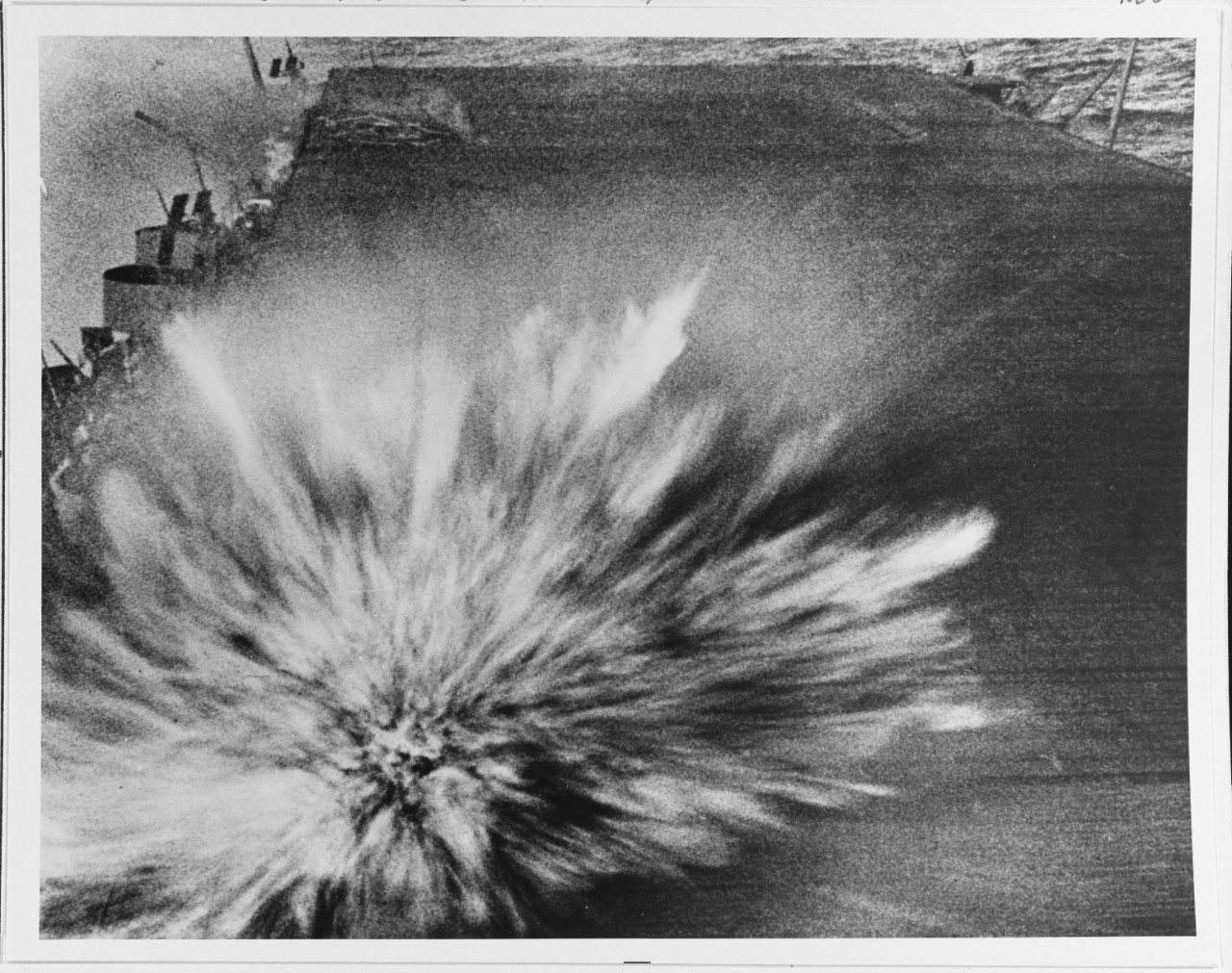

battle of the eastern solomons

August 23-25, 1942

As in the Coral Sea and at Midway, U.S. and Japanese ships never sighted each other during the course of this engagement—all attacks were carried out by carrier-based or shore-based aircraft. It was fought during Operation Ka, the Japanese counteroffensive against Allied landings in the eastern Solomons.

|

The Japanese wanted to launch a counter-offensive against the Allied forces for landing in the eastern Solomon Islands. Their plan was to reinforce their ground assets on Guadalcanal, but first they needed to destroy the Allied naval forces that were directly supporting the U.S. Marines on land. After a series of air attacks, neither were able to secure a clear victory. Both withdrew their naval forces from the area.

Despite withdrawing, U.S. forces gained tactical and strategic advantages on land. Japan lost a significant number of aircraft and personnel, and their goal of reinforcing their ground assets on Guadalcanal was delayed. As a result, the Allies were given time to rest and resituate their forces, and for months were able to prevent or interdict landings of the enemy's heavy artillery, ammunition, and other supplies.

|

A Japanese bomb exploding on the flight deck of USS Enterprise (CV-6) on August 24, 1942.

|

battle of edson ridge

12—14 Sep 1942

The Battle of Edson Ridge, also variously referred to as Lunga Ridge, Edson’s Ridge, and Bloody Ridge, was the attempt of the Imperial Japanese to regain control of Henderson Field by way of Lunga Ridge, a natural access point to the strategic airfield. Over the previous month the Empire of Japan had incrementally transported several thousand troops to Guadalcanal via an undefended supply corridor, referred to as the “Tokyo Express,” with the mission of retaking control of Henderson Field and driving the Allied forces from the island.

In response to the intelligence indicating a large enemy presence, 840 Marines from the 1st Marine Raider Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel Merritt (Red Mike) Edson, and the 1st Parachute Battalion were sent to defend the ridge. With limited resources due to the strong Imperial Japanese Naval presence, the Marines emplaced at the ridge and began preparing for the attack.

|

A historic photo shows the view of final line positions on Edson's Ridge in Guadalcanal. The lines barely held during the battle on Sept 13, 1942. The line is as viewed from Marine Corps Maj. Kenneth Bailey's intermediate position.

|

On the night of 12 Sept. 1942, following a bombardment of naval gunfire, more than 3,000 Imperial Japanese troops attacked the emplaced Marines at Lunga Ridge. Hours of intense close-range fighting led to the Imperial Japanese breaking through the Marines’ defenses before falling back for the evening, but retaining some ground gained during the engagement.

After a brief counterattack in the early hours led by the reserve companies, and having sustained heavy casualties after the bloody first engagement, the Marines were forced to fall back to consolidate and strengthen their defenses. Under the guidance of Lt. Col. Edson, the Marines fortified their position, requested the support of artillery, and rested in preparation for the next attack.

|

By nightfall, the Imperial Japanese had launched their attacks, with the Marines' counter-attacking at advancing assaults and making decisive adjustments at the direction of Lt. Col. Edson. Throughout the night and from numerous reorganized positions, the Marine line on the ridge grew weakened as they took more casualties with each attack, but continued to hold the ridge and the airfield. By 0400 on 14 Sept., 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, began providing companies to reinforce the Marines on the ridge, but the majority of attacking forces had been depleted.

By daybreak, the final attacks from the Imperial Japanese had been repelled, and the reinforced Marines on the ridge saw no more organized assaults and began driving remaining factions of enemy troops from the perimeter. Under the personal courage and inspirational leadership of Lt. Col. Edson and the heroic actions of the Marines, the Allies retained control of Edson Ridge and Henderson Field. The Imperial Japanese forces recognized defeat and retreated, having been rendered unable to complete their mission.

Battle of cape esperance

October 11, 1942

After more than a month without ground reinforcements, Japanese forces dispatched an extensive supply and reinforcement convoy to their ground forces on Guadalcanal on the night of October 11, 1942. Simultaneously, but independent of the resupply, three Japanese heavy cruisers and two destroyers planned to bomb Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, an airfield that U.S. Marines had taken upon landing on the island.

|

Shortly before midnight, U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Norman Scott sent a task force of four cruisers and five destroyers to surprise the Japanese naval forces as they approached Savo Island to the north of Guadalcanal's Cape Esperance. A Japanese cruiser and destroyer were sunk, with another cruiser badly damaged.

One U.S. destroyer was sunk, with one cruiser and destroyer in need of major repair. Retreating, the remaining Japanese ships abandoned their bombardment mission. Meanwhile, the Japanese supply convoy had successfully reached Guadalcanal without being discovered by Scott's task force. Although the engagement's strategic outcome remained inconclusive, the Battle of Cape Esperance helped the Allied naval forces recover momentum from previous losses in their defeat at Savo Island in early August.

|

The USS Boise arrives at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in November of 1942 for repair of battle damage received during the October 11-12 Battle of Cape Esperance. The USS Boise arrives at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in November of 1942 for repair of battle damage received during the October 11-12 Battle of Cape Esperance. |

Battle of santa cruz islands

October 26, 1942

Japanese naval forces in the Solomon Islands strategic area positioned themselves at the southern end of the Solomon Islands Chain in an attempt to distract allied naval forces from the major ground offensive being launched by the Japanese Army. On October 26, 1942, the U.S. and Japanese naval forces engaged each other just north of the Santa Cruz Islands, kicking off the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.

A Japanese Type 99 shipboard bomber (Allied codename Val) trails smoke as it dives toward USS Hornet (CV-8), during the morning of October 26, 1942.

|

Continuing a trend that would continue for the rest of the war, the opening stages of the battle were conducted by carrier aircraft attacking the opposing naval forces, with no warships firing directly at each other. U.S. ships were forced to retreat from the area, after suffering 81 aircraft lost, one destroyer sunk and two damaged, and a crippling loss of one aircraft carrier, as well as another heavily damaged.

Despite the significant damage caused to the U.S. naval force, the Japanese halted their assault after suffering 99 aircraft lost, and significant damage to many of their ships. The loss of these aircraft and their pilots, as well as the damage to the Japanese ships removed the Japanese carrier forces from the equation for the rest of the Guadalcanal campaign.

|

battle of Tassafaronga

November 30, 1942

The Battle of the Tassafronga Sea, also known as the Battle of Ironbottom Sound took place on November 30, 1942.

|

A U.S. Navy task force was able to use their newly designed surface search radar to locate Japanese ships in the area. Attempting to catch the Japanese by surprise, the U.S. task force attacked the enemy force and managed to sink a Japanese destroyer. Despite the U.S. force having an advantage due to the new radar, the Japanese were able to quickly react and fired off a large number of torpedoes at the U.S. ships.

These torpedoes met their target, and sank a U.S. cruiser, and caused heavy damage to three other cruisers. The Japanese forces used this as an opportunity to disengage from the U.S. ships, and were able to successfully withdraw from the immediate area. This tactical retreat came at the expense of the Japanese forces on the island of Guadalcanal, who the Japanese trips had been attempting to reinforce and resupply.

|

USS Minneapolis (CA-36) at Tulagi with torpedo damage received in the battle. Photograph was taken on December 1, 1942. USS Minneapolis (CA-36) at Tulagi with torpedo damage received in the battle. Photograph was taken on December 1, 1942. |

japanese withdrawal and u.s. victory

february 1943

Despite the allied losses during the naval battles of Guadalcanal, the increased presence of allied naval forces greatly hindered the Japanese navy’s ability to resupply their forces on Guadalcanal. In addition, allied aircraft from Henderson Field and aircraft carriers were able to stop multiple Japanese resupply attempts.

Japanese Transport KINUGAWA MARU beached and sunk on Guadalcanal, where she was destroyed by U.S. forces in November of 1942.

|

Despite the allied losses during the naval battles of Guadalcanal, the increased presence of allied naval forces greatly hindered the Japanese navy’s ability to resupply their forces on Guadalcanal. In addition, allied aircraft from Henderson Field and aircraft carriers were able to stop multiple Japanese resupply attempts.

The last success for the Japanese navy during the Guadalcanal campaign took place on January 29, 1943. Two Japanese air groups located and attacked allied Task Force 18, a formation of five cruisers and six destroyers. The cruiser USS Chicago was struck by two torpedoes launched by the Japanese aircraft, damaging her propulsion and leaving her unable to move. This engagement was dubbed the Battle of Rennell Island, and marked the beginning of the end for the Japanese at Guadalcanal.

|

After the continued losses at Guadalcanal, the Japanese high command came to the realization that withdrawal from the island was the best strategic move. Beginning in January 1943 the Japanese forces were evacuated by embarking on Japanese destroyers. The evacuations took place mostly during night, to avoid the risk of attack by allied air and naval forces. On the night of February 7, 1943 the last Japanese forces were evacuated from Guadalcanal.

Over the seven months of the Guadalcanal campaign, U.S. forces took startlingly high casualties, with 7,100 dead and almost 8,000 wounded. The Japanese forces defending the island suffered more than 19,000 personnel killed, with an unknown number wounded. After the daring amphibious landing at Guadalcanal, the months of bitter fighting through the dense jungle, and the harrowing naval battles, the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Navy struck the United States’ first substantial blow against the Japanese since the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the Guadalcanal campaign, the Japanese would be on the defensive in the Pacific for the remainder of the war.

Korea After World War II

At the end of World War II, the Indo-Pacific region was in disarray, devastated by fourteen years of brutal, ever-widening warfare. After four decades of domination and colonization by the Empire of Japan, the postwar Korean Peninsula was divided between the allied powers for the purposes of establishing interim transitional governments. With a dividing line drawn at the 38th Parallel, the Soviet Union agreed to take responsibility for the northern sector of the Peninsula and the United States for the southern. This division, originally intended to be temporary until national elections could be held, gradually solidified as stark ideological differences separated the governing authorities of the northern and southern sectors.

On 8 September 1945, the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) was established, inaugurating a three-year period of governance south of the 38th Parallel by U.S. military officers and civil servants. The USAMGIK period also saw the first democratic elections in Korean history on 10 May 1948, overseen by United Nations observers and facilitated by U.S. military personnel. With a mandate in place and representatives chosen, the Republic of Korea (ROK, commonly referred to as South Korea) was founded on 15 August 1948, terminating the American military government and bringing the southern half of Korea under sovereign and independent self-rule for the first time since Japanese colonization in 1905.

Korean War

25 June, 1950-27 July, 1953

On 25 June 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, commonly referred to as North Korea) crossed the 38th Parallel in force, with the mission of conquering the Republic of Korea and reunifying the peninsula under Communist rule. This invasion, undertaken with the acquiescence and foreknowledge of the Soviet Union and People’s Republic of China, achieved operational and strategic surprise, initially gaining considerable ground and pushing the Republic of Korea Armed Forces back. Responding to United Nations Resolution 83 which passed on 27 June and called for international military aid to defend the embattled Republic of Korea, U.S. forces entered the conflict as the main component of a United Nations mission to halt the DPRK’s aggression.

U.N. actions against the North Korean onslaught in the first weeks of the war were desperate and forlorn. ROK forces were ill-equipped for combat and lacked heavy weapons to confront modern Soviet-built KPA tanks. American units mustered rapidly from occupation troops in Japan were similarly unprepared, with minimal ammunition and air cover with which to mount counterattacks. Other elements of the United Nations coalition – 22 nations in all – took time to gather their forces and arrive in theater. The summer of 1950 became a series of rearguard actions, with U.N. forces losing ground everywhere. Forced to mount a fighting retreat all the way down the Peninsula, U.N. lines were eventually stabilized around a small pocket of land at Korea’s southeastern tip in the immediate environs of the city of Pusan (rendered in English as Busan today). The Pusan Perimeter, as it is known to posterity, was a last-ditch effort beyond which there was no retreat but the sea. Manned by understrength ROK infantry and hastily deployed U.S. Army formations, U.N. forces on the small Perimeter were nevertheless thinly stretched. The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade arrived on 2 August directly from the United States with 1st Marines, 5th Marines, and Marine Aircraft Group 33 in tow, but many Marines in these units were brand new from training and had to make do with the little training they had received from combat veterans on the ships over from San Diego.

Nevertheless, U.N. forces held on throughout August, 1950. LTG Walton Walker employed the Marines brilliantly as a mobile “fire brigade,” darting around at high speed to tamp down “hot spots” where the KPA threatened to break through the overstretched Perimeter. Yet no amount of brilliant maneuvering would be enough to stop the onslaught permanently. Fearing a perilous Dunkirk-style evacuation and the total loss of Korea to Communist forces, Supreme Allied Commander Douglas MacArthur developed a daring plan to cut North Korean supply lines, seize the initiative, and force a retreat of the cut-off Communist forces from around Busan. With this single stroke, MacArthur intended to turn the tide of the war.

Battle of Inchon (Operation Chromite)

September 15, 1950

All throughout August and into September, 1950, ships of all sizes and nations arrived in Tokyo Bay. Though MacArthur’s nascent operation had been planned in secret, eventually the flotilla became so large that reporters in the area referred to the buildup as “Operation Common Knowledge.” The obviousness of this enormous presence was only somewhat mitigated by U.N. forces’ diversionary tactics; Soviet and Chinese intelligence both warned the North Korean leadership of an imminent landing.

Yet the brazenness of the planned U.N. landing location – a port city about halfway up the western side of the Korean Peninsula called Inchon – confounded predictions. Inchon was a highly dangerous site for an amphibious landing: a rocky harbor with some of the most extreme tides in the world, swinging between high and low approximately thirty feet in total. These risks initially generated strong skepticism of the plan from professionals in the Naval Service; General MacArthur fought hard to convince Navy and Marine leaders of the merits of his bold stroke. Such a fight had to be won for the plan to work: from the beginning, MacArthur intended to rely on the Marines at Inchon for their proficiency in amphibious warfare. By the time the plan was finally approved, MacArthur even went so far as to hand-select the 1st Marine Division to lead the assault. Operation Chromite, one of the most daring amphibious operations in history, was slated to begin on 15 September.

|

Starting on 10 September, U.N. aircraft commenced preparatory attacks on islands near Inchon. Striking at KPA formations on the hillsides, these flights also provided valuable reconnaissance information for the invasion fleet as it steamed up the Korean coast. When advance naval elements arrived on 13 September, carrier-based aircraft squadrons, destroyers, and cruisers initiated a two day bombardment against KPA in the Inchon area, hitting fortifications, artillery batteries stationed at the coast, and supply points. This barrage caught KPA forces largely unprepared; North Korean leadership had failed to shift sufficient forces to the Inchon area before the U.N. armada arrived, and what few units were in the area were unable to effectively counter the heavy naval guns that now assailed their defenses.

Then, on 15 September, the landings began. The combined Army-Marine invasion forces of X Corps initiated the assault across three beaches termed Red, Blue, and Green, clambering over seawalls with improvised ladders and up hillsides defended by North Korean machine gun teams. Combat was fierce, damaging several large LSTs and even sinking one as they transported invasion waves ashore. By noon, Marines of 3/5 and 1st Tank Battalion at Green Beach had seized Wolmi-do – an island with a commanding position overlooking all of Inchon harbor – allowing subsequent echelons to come ashore. Red Beach and Blue Beach were next, as 1/5, 2/5, and all of 1st Marines joined the fight. Notably, U.S. Marines landing at Red Beach were augmented by a full battalion of ROK Marines, marking the first time the two nations’ Corps conducted amphibious operations together. Here as well, fighting was intense as KPA forces sought in vain to resist the surprise invasion. Yet by evening, X Corps had come ashore in such strength and moved with such speed that North Korean forces had been pushed back from all three objective areas. After repelling hasty counterattacks during the night, U.N. forces were in uncontested control of the Inchon beachhead by the morning of 16 September. Operation Chromite, a daring leap onto the enemy’s back in one of the most dangerous places imaginable, had been a stunning success within twenty-four hours of landing.

When that 16 September morning arrived, new orders were issued to exploit the KPA’s vulnerability and capitalize on X Corps’ commanding advantage. Strikes deep inland began immediately, aiming first at Kimpo airfield between Inchon and Seoul to establish a base for U.N. land-based aviation. The airfield was captured by Marines on 17 September, who then fended off continued KPA attacks throughout that night. Fighting intensified as the main body of U.N. forces neared Seoul and KPA reinforcements arrived, including tanks and aircraft to support Communist counterattacks. Once battle was joined on the urban terrain of Seoul itself, the pace of the U.N. offensive slowed considerably; tooth-and-nail fighting in this built-up area against dug-in forces turned the battle for the ROK capital city into a grinding ordeal. Yet by 28 September, KPA forces had been driven out of Seoul at last. Collapsing Communist lines further south also allowed a final breakout by American and ROK units still inside the Pusan Perimeter. In just two weeks, Operation Chromite had transformed the Korean War from a U.N. near-defeat to a rout of the invading Communists. Today, the Inchon Landing is remembered as a testament to the effectiveness of amphibious operations, as a resounding success born of U.S.-ROK cooperation, and as one of the proudest moments in the history of the United States Marine Corps.

|

First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez, USMC, leads the 3rd Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines over the seawall on the northern side of Red Beach, as the second assault wave lands, 15 September 1950. Wooden scaling ladders are in use to facilitate disembarkation from the LCVP that brought these men to the shore. Lt. Lopez was killed in action within a few minutes, while assaulting a North Korean bunker. U.S. Marine Corps Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command.

|

the fall of french indochina

During a period of overseas colonialization, the government of France established control of Vietnam in 1887. During WWII, the Empire of Japan sought to gain control of the region and utilize the resources available and within a year, a radical communist liberation movement, known as Việt Nam Độc lập Đồng minh, or Viet Minh for short, was founded to fight the Japanese occupation of Vietnam. Following Japanese defeat, most countries of Southeast Asia, formerly occupied by Japan, protested their return to colonial status, causing a rise in Nationalism.

By the late 1940s, France struggled to retain control of its colonies in Indochina, ultimately proposing autonomy to Vietnam with limited independence in 1949. Concerned with the popularity and influence of nationalist Ho Chi Minh, the French proposed reinstatement of former emperor Bao Dai, ultimately fueling the independence movement in Vietnam and conflict ensued following unsuccessful discussions in 1946 between the French and Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh forces.

After a decisive loss from the French at Dien Bien Phu, representatives from France, Vietnam, the United States, and China met at the 1954 Geneva Conference to discuss the future of Indochina. Agreements were made in which France and Vietnam agreed to a ceasefire and a temporary division of the country along the 17th parallel. The division saw Ho Chi Minh’s forces controlling the North, while French forces would remain in the south under the locally run colonial government. The final agreement called for neither the North nor South to join alliances with outside parties and to hold general elections for a unified government in 1956.

u.s. intervention

Following the communist rebellions in Malaya and the Philippines, and the establishment of the People`s Republic of China in 1949, the United States felt great concern for communist expansion into Vietnam. President Eisenhower referred to the status of Vietnam and communism in the region as a “domino effect”, stating that if one country fell to communism, the remaining would follow. With the fear of communist expansion, along with the commitment to defending the French against the Viet Minh forces, the United States did not sign the alliance and election agreement at the 1954 Geneva Conference and established a government in South Vietnam.

As the French evacuated from Vietnam, the United States appointed Ngo Dinh Diem to lead in South Vietnam and endorsed the decision to withdraw from the 1956 elections, believing that the elections would likely lead to a unified Vietnam under communist control. The refusal to hold elections in accordance with the 1954 Geneva Conference sparked an increase in activities form the Viet Minh forces.

As the unrest turned to conflict between the Southern Army of the Republic of Vietnam and the Northern Viet Minh forces, the United States sought to defend the non-communist South Vietnamese government and began providing material support and military advisors. The most successful military advisors were U.S. Army Green Berets and the U.S. Marine Corps. Able to pass on advanced knowledge on small unit tactics and lessons learned from campaigns in Nicaragua, Haiti, and China, the military advisors proved to be a strong asset in supporting the non-communist government in South Vietnam.

On August 2, 1964, two U.S. destroyers stationed in the Gulf of Tonkin in Vietnam radioed that they had been fired upon by North Vietnamese torpedo boats, with the USS Madox reporting a second attack, stating they were under “continuous topedo attack”. On August 7, 1964, U.S. Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, authorizing President Lyndon B. Johnson to take any actions needed to retaliate and promote international peace and security within Southeast Asia, officially bringing the United States into the Vietnam War.

Colonel John A. MacNeil, senior Marine advisor, inspects Vietnamese Marines' M-1 rifles. Material readiness was a matter of primary concern for the Marine Advisory Unit in 1965.

da nang

On March 8, 1965, a Marine Corps Special Landing Force, built around the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, was sent in to provide a reinforcement of the U.S. Air Force Base in Da Nang. These Marines were the first American ground-combat troops committed to the Vietnam War. The movement began when 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines conducted an amphibious landing at My Khe Beach, just south of Da Nang. Hours later, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, inserted to the west of Da Nang by helicopter. The Marines had been requested by U.S. Army General William C. Westmoreland, commander-in-chief of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), after a series of major Viet Cong bombings and raids in the area. This increase of forces and the shift from Marines conducting an advisory role to full-fledged combat marked a turning point in the United States’ commitment to the war in Vietnam. The committed Marine forces saw their first combat operation in August of 1965 with Operation Starlite.

operation starlite

On August 18, 1965, thousands of Marines embarked on the first major Marine Corps battle in the Vietnam War: Operation Starlite. The operation was the first large battle of the war that was conducted solely by Marines fighting the communist Northern Vietnam forces. The success of Operation Starlite hinged on a tried-and-true military tactic: the hammer and anvil. Company M, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines would act as a blocking force or “anvil” to the north of the engagement area, positioned to prevent any communist forces from fleeing the area. While to the south, the rest of 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines would conduct an amphibious landing just as 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines landed by helicopter. These units would assault the enemy Viet Cong positions and “hammer” them into the blocking force. The speed at which the Marines were able to bring their full strength into the fight caught the communist forces off guard, and within a handful of days, Operation Starlite was ended when the 1st Viet Cong Regiment withdrew from the area.

the tet offensive

The Vietnamese Lunar New Year, known as Tết Nguyên Đán, or Tet for short, was and is the most significant celebration in Vietnamese culture. Celebrated by Vietnamese of all backgrounds, in the first years of the Vietnam War, Tet had been honored with a three-day long truce by both communist and democratic forces. In 1968, wanting to take advantage of the traditional cease fire, North Vietnam devised a cunning plan: seize a handful of ARVN bases immediately before Tet, and use the three-day truce to resupply and fortify these holdings. As planning for the attacks progressed, the goal instead became to launch dozens of coordinated attacks in an attempt to destroy the American will to fight and unite the Vietnamese people under the communist North. Shortly after midnight on January 30th, 1968, the Viet Cong and PAVN unilaterally broke the cease fire and launched attacks across South Vietnam. These attacks were highly coordinated and caught the U.S. and ARVN forces off guard, allowing the communist forces to make large gains early on in the fighting. The Tet Offensive set the stage for some of the fiercest battles in Marine Corps history, from the bloody urban fighting in Hue City, to the month long siege at Khe Sanh. Despite being an overall tactical loss for the NVA and Viet Cong, the Tet Offensive succeeded in its goal of weakening American support for the war in Vietnam.

Battle of khe sanh

Located 14 miles south of the DMZ near the village of Khe Sanh and defended by roughly 6,000 Marines, the Khe Sanh combat base was attacked in early 1968, by 20,000 soldiers from three separate North Vietnamese Army regiments.

The first major engagement of the battle took place on January 20, 1968, with a coordinated mortar and artillery attack led by the NVA on a U.S. outpost located on Hill 861. The engagement culminated with an attack from around 300 infantry fighters, resulting in bloody close-range fighting with the Marines from Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines. The Marines from Kilo Company were able to hold the NVA offensive until Marine artillery and air support ultimately repelled the attack.

Throughout the battle, various methods of supporting and supplying the Marines at Khe Sanh were implemented, including Operation Niagara, in which the U.S. Air Force dropped over 100,000 bombs, in conjunction to 158,000 rounds of artillery into NVA positions around the base.

After months of fighting, a combined Marine-Army/ARVN task force relief expedition, Operation Pegasus, reached the Marines at Khe Sanh on April 14, 1968, and the defense was considered a success. However, amidst continuous attacks and artillery, the decision to dismantle the base and evacuate all personnel was made as to not risk a similar battle again.

Khe Sanh would continue to see combat until the end of July 1968, after which the base was destroyed and abandoned by American forces.

Khe Sanh, South Vietnam, an isolated United States Marine Corps out post during the Vietnam War became too dangerous to land due to hostile ground fire and shelling. To accommodate, C-130s used the Low Altitude Extraction System and kept the Marines resupplied with rations, fuel, ammunition and medical supplies.